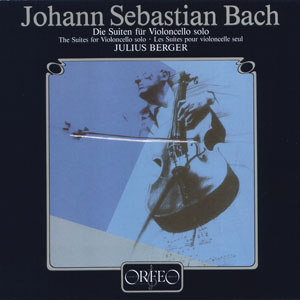

Johann Sebastian Bach

Die Suiten für Violoncello solo

Orfeo • 2 CD • 2h 25min

GRAMOPHONE

Bach’s instrumental music seems happily responsive to the evolving ideas of single interpreters: witness Wolfgang Rubsam, who significantly revised his tempos, phrasing and rubato (compare his Philips and Naxos recordings of Bach’s organ works); or Glenn Gould, who could change his mind between takes – and now the distinguished German-born cellist Julius Berger who, although still only in his mid-40s, has done what often amounts to an interpretative volte-face with Bach’s Cello Suites. Berger’s first (1984) recording of the Suites, issued by Orfeo in 1985, was more formal in style, more studied and tuned at a higher pitch, though even then a telling blend of phrasal individuality and stylistic awareness made a strong impression. Orfeo’s recording was fairly dry, whereas this new one, made in the accommodating acoustic of San Vigilio near Col San Martin with distant birds chirruping among the eaves (Wergo’s annotator writes of “an atmosphere of inspiration and calm”), is more full-bodied, albeit with more audible fingerwork. In the Sixth Suite, Berger plays the same five-string cello that he used for the whole of his Orfeo set (Jan Pieter Rambouts, Amsterdam 1700), while in the other five he opts for a beautiful Johan Baptist Guadagnini instrument, ex-Davidoff, Turin 1780.

In terms of performance, the tone is lighter than before; inflexions are keener; the overall approach is more appreciative of the dance origins of many movements, and chosen tempos are generally (though not always) faster. The contrasts in speed are most marked in the Prelude to the Fourth Suite, which here is a nifty 3’32” staccato as opposed to a broad 6’52” legato back in 1984. Sarabandes now resemble stately processionals and, in the Sixth Suite, Berger transforms what was a 12’04” Allemande into a more reasonable 7’07” (both performances include the two repeats). Very occasionally, the older set harbours the swifter tempos, but more often than not Berger’s new-found spontaneity suggests the sort of fluid improvisation that Bach himself so often enjoyed. Articulation is mostly precise, though the earlier version of the Third Suite’s closing Gigue is marginally cleaner. Vibrato is used very sparingly, more often in the faster movements than in the slower ones, and the phases of experimentation that Berger refers to in his booklet-note (relating to vibrato, strings, bows, ways of actually holding the instrument – and perhaps a minor harmonic alteration 0’14” into the Sixth Suite’s first Gavotte) appear to have widened the scope of his playing.

Wergo’s attractive gatefold presentation quotes Couperin, Mattheson, Brossard, Quantz, Hindemith and Gubaidulina on the character of Bach’s music. Berger himself speaks of a “joy inspired by the most radiant peak of tonal art”, and anyone listening will happily concur. It is indeed a wonderful set, more free spirited than its predecessor (though I shall want to retain both) and, for me, more compelling than most modern rivals, excepting Janos Starker (his fourth recording) and Anner Bylsma (his second). I urge you to hear it.’